When the Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ was announced in March of 2018, one of its new features was the ability to be (more easily) powered via Power-over-Ethernet (PoE), with an official PoE HAT for the low price of just twenty-one USA bucks. The thing also almost worked as intended the first time around. But to some people this just isn’t good enough, resulting in [Albert David] putting out a solution he calls “poor man’s PoE” together for about two bucks.

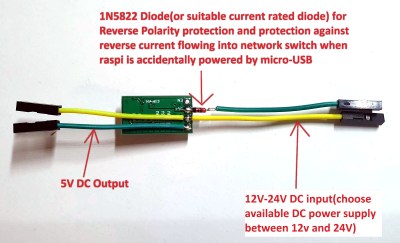

His solution makes it extra cheap by using so-called passive PoE, which injects a voltage onto the conductors of the network cable being used for PoE, without bothering with any kind of handshake. In general this is considered to be a very reliable (albeit non-standard) form of PoE that works great until something goes up in smoke. It’s also ridiculously cheap, with a PoE injector adapter (RJ-45 plug & 2.1×5.5 mm power jack to RJ-45 jack) going for about 80 cents, and a DC-DC buck converter that can handle the input of 12V for about 50 cents.

The rest of the $2 budget is mostly spent on wiring and heatshrink, resulting in a very compact PoE solution that plugs straight into the PoE header on the Raspberry Pi 3 board, with the buck converter outputs going into the ground and +5V pins on the Raspberry Pi’s GPIO header.

The rest of the $2 budget is mostly spent on wiring and heatshrink, resulting in a very compact PoE solution that plugs straight into the PoE header on the Raspberry Pi 3 board, with the buck converter outputs going into the ground and +5V pins on the Raspberry Pi’s GPIO header.

A fancier solution would implement any of the standard PoE protocols to do the work of negotiating a suitable voltage. Maybe this could be the high-tech, $5 solution featuring an MCU and a small PCB?

from Hackaday https://ift.tt/2mcxoIW

Comments

Post a Comment